Merken magazine

Sustainable Art

The path of art and sustainability is like a spiral, it goes through cycles of learning, unlearning, and reimagining. This gallery celebrates artists who go into circles and circles to transform what has been deemed as waste into beauty and wisdom.

Climate anxiety is increasing with every year, almost haunting our collective conscience. Something calming would be to celebrate the artists who merge art and environmental care. They transform discarded materials into … works that speak of renewal, resilience, sense of community, and responsibility. Beauty can, indeed, grow from what‘s dirty, broken, and harmful. Just as many other fields need to be reimagined for a greener future, art, with its ability to shape life, must contribute.

(2006)

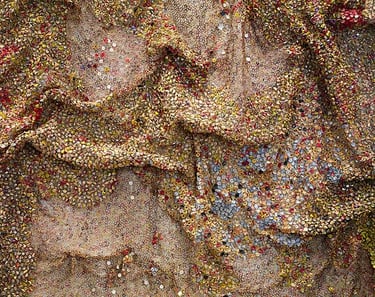

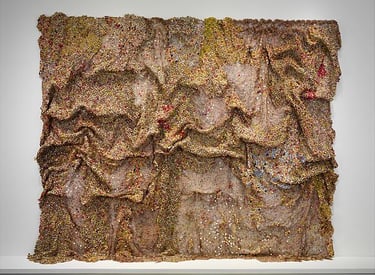

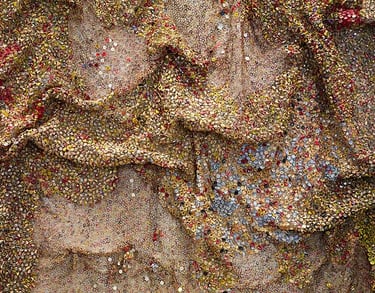

Historically, these materials link to colonial trade: European alcohol was used as currency in the slave trade, and the caps “encapsulate the essence” of that fraught history.

Image Source: El Anatsui. Dusasa II. 2007. Aluminum and copper wire. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of the Artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, 2008 (2008.8). Public domain.

Chazen Museum of Art. "Bulletin 2003-2007." Madison: Chazen Museum of Art, 2010. p. 39, no. 3

El Anatsui

Ghanaian sculptor, El Anatsui, takes cast-off materials and transforms them into glittering tapestries, turning trash into mesmerizing beauty and creating an expansive cloth-like sheet whose colors and patterns evoke traditional kente cloth as well as modern consumer waste.

His monumental tapestry Dusasa II is assembled from thousands of discarded liquor-bottle caps and seals, flattened and painstakingly joined with copper wire . The shimmering, cloth-like sculpture evokes the tradition of West African kente textiles even as its material speaks to the detritus of consumerism.

Dusasa

Danu

The process includes him and his assistants collecting, cleaning, pounding, and weaving the metal fragments without harmful chemicals, giving new life to materials otherwise bound for scrap.

By transforming waste into a work of opulent beauty, El Anatsui creates a “communal patchwork” that bridges local craft and global consumption, celebrating reuse while commenting on the excesses of contemporary life.

Artistically, the draped metallic tapestry invites comparisons to both textiles and mosaics.

(2006)

(2006)

Historically, these materials link to colonial trade: European alcohol was used as currency in the slave trade, and the caps “encapsulate the essence” of that fraught history.

Image Source: El Anatsui. Dusasa II. 2007. Aluminum and copper wire. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of the Artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, 2008 (2008.8). Public domain.

Chazen Museum of Art. "Bulletin 2003-2007." Madison: Chazen Museum of Art, 2010. p. 39, no. 3

El Anatsui

Ghanaian sculptor, Ek Anatsui, takes cast-off materials and transforms them into glittering tapestries, turning trash into mesmerizing beauty and creating an expansive cloth-like sheet whose colors and patterns evoke traditional kente cloth as well as modern consumer waste.

His monumental tapestry Dusasa II is assembled from thousands of discarded liquor-bottle caps and seals, flattened and painstakingly joined with copper wire . The shimmering, cloth-like sculpture evokes the tradition of West African kente textiles even as its material speaks to the detritus of consumerism .

Dusasa

Danu

The process includes him and his assistants collecting, cleaning, pounding, and weaving the metal fragments without harmful chemicals, giving new life to materials otherwise bound for scrap.

By transforming waste into a work of opulent beauty, El Anatsui creates a “communal patchwork” that bridges local craft and global consumption, celebrating reuse while commenting on the excesses of contemporary life.

Artistically, the draped metallic tapestry invites comparisons to both textiles and mosaics.

(2006)

El Anatsui

Ghanaian sculptor, Ek Anatsui, takes cast-off materials and transforms them into glittering tapestries, turning trash into mesmerizing beauty and creating an expansive cloth-like sheet whose colors and patterns evoke traditional kente cloth as well as modern consumer waste.

(2006)

Historically, these materials link to colonial trade: European alcohol was used as currency in the slave trade, and the caps “encapsulate the essence” of that fraught history.

Image Source: El Anatsui. Dusasa II. 2007. Aluminum and copper wire. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of the Artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, 2008 (2008.8). Public domain.

Chazen Museum of Art. "Bulletin 2003-2007." Madison: Chazen Museum of Art, 2010. p. 39, no. 3

His monumental tapestry Dusasa II is assembled from thousands of discarded liquor-bottle caps and seals, flattened and painstakingly joined with copper wire . The shimmering, cloth-like sculpture evokes the tradition of West African kente textiles even as its material speaks to the detritus of consumerism.

Dusasa

Danu

The process includes him and his assistants collecting, cleaning, pounding, and weaving the metal fragments without harmful chemicals, giving new life to materials otherwise bound for scrap.

By transforming waste into a work of opulent beauty, El Anatsui creates a “communal patchwork” that bridges local craft and global consumption, celebrating reuse while commenting on the excesses of contemporary life.

Artistically, the draped metallic tapestry invites comparisons to both textiles and mosaics.

(2006)

(1982–1987, Kassel, Germany)

The 7000 Oaks was conceived as a growing “social sculpture,” as unveiled at Documenta 7 in 1982. The process of the art work included 5 years of Beuys and other volunteers and locals expanding forests into city streets. They completed the project at Documenta 8 in 1987. The effort was supported by the Dia Art Foundation and it was intended as just the first phase of a worldwide afforestation initiative as Beuys imagined tree-planting spreading across the planet as an ever-growing artwork to spur environmental and social change.

Images available under Public License; File:7000 Eichen - Hafenstraße 2019-08-24 b.JPG - Wikimedia Commons. (2019, August 24). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:7000_Eichen_-_Hafenstra%C3%9Fe_2019-08-24_b.JPG#filelinks

Joseph Beuys

This land artwork is of the most ambitious ecological art interventions of the 20th century as the German artist Joseph Beuys planted, throughout the city of Kassel, 7000 oak trees, each paired with columnar basalt stone.

Artistically, 7000 Oaks redefined public sculpture: the “artwork” is not only the trees themselves but the participatory process and ecological legacy. Beuys explicitly framed it as a permanent installation that would continue to grow and absorb CO₂, literally greening the city. In his words, it was a call to reshape society “Stadtverwaldung statt Stadtverwaltung” (urban forestation instead of city administration)

7000 Oaks

Joseph Beuys

This land artwork is of the most ambitious ecological art interventions of the 20th century as the German artist Joseph Beuys planted, throughout the city of Kassel, 7000 oak trees, each paired with columnar basalt stone.

(1982–1987, Kassel, Germany)

The 7000 Oaks was conceived as a growing “social sculpture,” as unveiled at Documenta 7 in 1982. The process of the art work included 5 years of Beuys and other volunteers and locals expanding forests into city streets. They completed the project at Documenta 8 in 1987. The effort was supported by the Dia Art Foundation and it was intended as just the first phase of a worldwide afforestation initiative as Beuys imagined tree-planting spreading across the planet as an ever-growing artwork to spur environmental and social change.

Images available under Public License; File:7000 Eichen - Hafenstraße 2019-08-24 b.JPG - Wikimedia Commons. (2019, August 24). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:7000_Eichen_-_Hafenstra%C3%9Fe_2019-08-24_b.JPG#filelinks

Artistically, 7000 Oaks redefined public sculpture: the “artwork” is not only the trees themselves but the participatory process and ecological legacy. Beuys explicitly framed it as a permanent installation that would continue to grow and absorb CO₂, literally greening the city. In his words, it was a call to reshape society “Stadtverwaldung statt Stadtverwaltung” (urban forestation instead of city administration)

7000 Oaks

(1982–1987, Kassel, Germany)

The 7000 Oaks was conceived as a growing “social sculpture,” as unveiled at Documenta 7 in 1982. The process of the art work included 5 years of Beuys and other volunteers and locals expanding forests into city streets. They completed the project at Documenta 8 in 1987. The effort was supported by the Dia Art Foundation and it was intended as just the first phase of a worldwide afforestation initiative as Beuys imagined tree-planting spreading across the planet as an ever-growing artwork to spur environmental and social change.

Images available under Public License; File:7000 Eichen - Hafenstraße 2019-08-24 b.JPG - Wikimedia Commons. (2019, August 24). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:7000_Eichen_-_Hafenstra%C3%9Fe_2019-08-24_b.JPG#filelinks

Joseph Beuys

This land artwork is of the most ambitious ecological art interventions of the 20th century as the German artist Joseph Beuys planted, throughout the city of Kassel, 7000 oak trees, each paired with columnar basalt stone.

Artistically, 7000 Oaks redefined public sculpture: the “artwork” is not only the trees themselves but the participatory process and ecological legacy. Beuys explicitly framed it as a permanent installation that would continue to grow and absorb CO₂, literally greening the city. In his words, it was a call to reshape society “Stadtverwaldung statt Stadtverwaltung” (urban forestation instead of city administration)

7000 Oaks

(1982, New York City, USA)

‘A Confrontation’ is a project that involved months of labor of Denes and other volunteers hand-clearing rubble, laying topsoil, digging 285 furrows, and sowing wheat by hand on land valued at billions of dollars. The confrontation comes from the sight of golden stalks of grain ripening amidst skyscrapers creating a jarring paradox and iconic images, a symbolic confrontation with “High Civilization” and “forgotten values” against the metrics of urban wealth.

Image Source: Agnes Denes, Wheatfield—A Confrontation. Two acres of wheat planted and harvested by the artist on the Battery Park landfill, Manhattan, Summer 1982. Commissioned by Public Art Fund.Photo by John McGrall. Courtesy the artist and Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects.

Wheatfield – A Confrontation: Battery Park Landfill, Downtown Manhattan, Aerial View, 1982. © the artist. Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, New York

Agnes Denes

Wheatfield is an ecological artwork created by Agnes Denes in the summer of 1982, at the dawn of the 1980s environmental art movement. On the empty landfill of Battery Park City and in the shadow of Manhattan’s financial district, a two-acre wheat field was planted and harvested.

Denes highlighted issues of land use and mismanagement of resources. Denes distributed the harvested grain worldwide as part of The International Art Show for the End of World Hunger, and the seeds were replanted across continents.

Wheatfield - A Confrontation

(1982, New York City, USA)

Wheatfield is an ecological artwork created by Agnes Denes in the summer of 1982, at the dawn of the 1980s environmental art movement. On the empty landfill of Battery Park City and in the shadow of Manhattan’s financial district, a two-acre wheat field was planted and harvested.

Image Source: Agnes Denes, Wheatfield—A Confrontation. Two acres of wheat planted and harvested by the artist on the Battery Park landfill, Manhattan, Summer 1982. Commissioned by Public Art Fund.Photo by John McGrall. Courtesy the artist and Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects.

Wheatfield – A Confrontation: Battery Park Landfill, Downtown Manhattan, Aerial View, 1982. © the artist. Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, New York

Agnes Denes

This land artwork is of the most ambitious ecological art interventions of the 20th century as the German artist Joseph Beuys planted, throughout the city of Kassel, 7000 oak trees, each paired with columnar basalt stone.

‘A Confrontation’ is a project that involved months of labor of Denes and other volunteers hand-clearing rubble, laying topsoil, digging 285 furrows, and sowing wheat by hand on land valued at billions of dollars. The confrontation comes from the sight of golden stalks of grain ripening amidst skyscrapers creating a jarring paradox and iconic images, a symbolic confrontation with “High Civilization” and “forgotten values” against the metrics of urban wealth. Denes highlighted issues of land use and mismanagement of resources. Denes distributed the harvested grain worldwide as part of The International Art Show for the End of World Hunger, and the seeds were replanted across continents .

Wheatfield - A Confrontation

Agnes Denes

Wheatfield is an ecological artwork created by Agnes Denes in the summer of 1982, at the dawn of the 1980s environmental art movement. On the empty landfill of Battery Park City and in the shadow of Manhattan’s financial district, a two-acre wheat field was planted and harvested.

(1982, New York City, USA)

‘A Confrontation’ is a project that involved months of labor of Denes and other volunteers hand-clearing rubble, laying topsoil, digging 285 furrows, and sowing wheat by hand on land valued at billions of dollars. The confrontation comes from the sight of golden stalks of grain ripening amidst skyscrapers creating a jarring paradox and iconic images, a symbolic confrontation with “High Civilization” and “forgotten values” against the metrics of urban wealth.

Image Source: Agnes Denes, Wheatfield—A Confrontation. Two acres of wheat planted and harvested by the artist on the Battery Park landfill, Manhattan, Summer 1982. Commissioned by Public Art Fund.Photo by John McGrall. Courtesy the artist and Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects.

Wheatfield – A Confrontation: Battery Park Landfill, Downtown Manhattan, Aerial View, 1982. © the artist. Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, New York

Denes highlighted issues of land use and mismanagement of resources. Denes distributed the harvested grain worldwide as part of The International Art Show for the End of World Hunger, and the seeds were replanted across continents

Wheatfield - A Confrontation

(2005, Beijing, China; traveled internationally)

Waste Not presents over 10,000 items that were organized and saved by Song’s mother, Zhao Xiangyuan, over decades, varying from worn clothes and broken appliances to jars, soap, and plastic bags. The work pays tribute to an ethic born from hardship, shaped by the Cultural Revolution’s motto “wu jin qi yong” (waste not), in an era of scarcity where nothing was thrown away.

Image Source: ZHAO Xiangyuan (1938 – 2009) and SONG Dong Waste Not – wu jin qi yong, 2005 – ongoing Diverse materials and objects by SONG Dong and Tokyo Gallery + BTAP Photo: Katja Illne

Photo of Song Dong’s "Waste Not" by Tom Page, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Song Dong

Chinese artist Song Dong transforms objects that are an entire lifetime’s worth of savings into an immersive installation about memory, thrift, and sustainability. First the work was created in Beijing and later it was exhibited internationally.

It first began as a personal act of healing after his father’s death, and later became a poignant, traveling portrait of generational resilience. The installation invites viewers into a museum of ordinary life that challenges consumer culture and celebrates the quiet sustainability of reuse. The installation, artistically, is both orderly and overwhelming. It has been described as a kind of museum of everyday life as visitors often find it sparks memories of their own family possessions, triggering thoughts about what we truly need. Waste Not neither glamorizes nor condemns the items on display. Instead, it asks us to reconsider the life-cycle of objects and honors an ethos of sustainable living born from necessity.

Waste Not

(2005, Beijing, China; traveled internationally)

Waste Not presents over 10,000 items that were organized and saved by Song’s mother, Zhao Xiangyuan, over decades, varying from worn clothes and broken appliances to jars, soap, and plastic bags. The work pays tribute to an ethic born from hardship, shaped by the Cultural Revolution’s motto “wu jin qi yong” (waste not), in an era of scarcity where nothing was thrown away.

Image Source: ZHAO Xiangyuan (1938 – 2009) and SONG Dong Waste Not – wu jin qi yong, 2005 – ongoing Diverse materials and objects by SONG Dong and Tokyo Gallery + BTAP Photo: Katja Illne

Photo of Song Dong’s "Waste Not" by Tom Page, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Song Dong

Chinese artist Song Dong transforms objects that are an entire lifetime’s worth of savings into an immersive installation about memory, thrift, and sustainability. First the work was created in Beijing and later it was exhibited internationally.

It first began as a personal act of healing after his father’s death, and later became a poignant, traveling portrait of generational resilience. The installation invites viewers into a museum of ordinary life that challenges consumer culture and celebrates the quiet sustainability of reuse. The installation, artistically, is both orderly and overwhelming. It has been described as a kind of museum of everyday life as visitors often find it sparks memories of their own family possessions, triggering thoughts about what we truly need. Waste Not neither glamorizes nor condemns the items on display. Instead, it asks us to reconsider the life-cycle of objects and honors an ethos of sustainable living born from necessity.

Waste Not

Song Dong

Chinese artist Song Dong transforms objects that are an entire lifetime’s worth of savings into an immersive installation about memory, thrift, and sustainability. First the work was created in Beijing and later it was exhibited internationally.

(2005, Beijing, China; traveled internationally)

Waste Not presents over 10,000 items that were organized and saved by Song’s mother, Zhao Xiangyuan, over decades, varying from worn clothes and broken appliances to jars, soap, and plastic bags. The work pays tribute to an ethic born from hardship, shaped by the Cultural Revolution’s motto “wu jin qi yong” (waste not), in an era of scarcity where nothing was thrown away.

Image Source: ZHAO Xiangyuan (1938 – 2009) and SONG Dong Waste Not – wu jin qi yong, 2005 – ongoing Diverse materials and objects by SONG Dong and Tokyo Gallery + BTAP Photo: Katja Illne

Photo of Song Dong’s "Waste Not" by Tom Page, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

It first began as a personal act of healing after his father’s death, and later became a poignant, traveling portrait of generational resilience. The installation invites viewers into a museum of ordinary life that challenges consumer culture and celebrates the quiet sustainability of reuse. The installation, artistically, is both orderly and overwhelming. It has been described as a kind of museum of everyday life as visitors often find it sparks memories of their own family possessions, triggering thoughts about what we truly need. Waste Not neither glamorizes nor condemns the items on display. Instead, it asks us to reconsider the life-cycle of objects and honors an ethos of sustainable living born from necessity.

Waste Not

(2015–ongoing, global project)

They work in a way that during the daytime, the solar radiation heats the air inside, which makes them rise, and at night, they can drift on thermal currents. These poetic floating pods are envisioned to be the “longest, most sustainable journey around the world,” carried only by wind and sun. Conceptually, Aerocene is as much about community and open innovation as it is about the physical sculptures. It operates as an open-source project and a movement for a fossil-free future.

Image Source: “Fly with Aerocene Pacha” by Studio Tomás Saraceno / Aerocene Foundation, licensed under CC BY‑SA 4.0

Photo of the Aerocene Backpack by Studio Tomás Saraceno (2016/2017), licensed under CC BY‑SA 4.0, via Aerocene.org.

Tomás Saraceno

Argentine contemporary artist Tomás Saraceno’s Aerocene is a visionary art project that combines art, science, and environmental advocacy. Launched in 2015 during the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21) in Paris, Aerocene consists of a series of airborne sculptures, that are essentially large, balloon-like aerosolar vessels, that lift off the ground using only the heat of the sun and the air currents, without any fossil fuels, engines, or even helium and using recyclable materials.

With this, it invites scientists, engineers, and the public to collaborate on developing aerosolar flight technology. The Aerocene balloons have set world records for solar flight and have even lifted human passengers (in 2020, the Aerocene Pacha carried a person aloft without propane or engines, a first in aviation. In artistic terms, Saraceno extends the legacy of art-utopias like Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic visions or Ant Farm’s inflatable structures, but grounds it in climate urgency.

Aerocene

(2015–ongoing, global project)

They work in a way that during the daytime, the solar radiation heats the air inside, which makes them rise, and at night, they can drift on thermal currents. These poetic floating pods are envisioned to be the “longest, most sustainable journey around the world,” carried only by wind and sun. Conceptually, Aerocene is as much about community and open innovation as it is about the physical sculptures. It operates as an open-source project and a movement for a fossil-free future.

Image Source: “Fly with Aerocene Pacha” by Studio Tomás Saraceno / Aerocene Foundation, licensed under CC BY‑SA 4.0

Photo of the Aerocene Backpack by Studio Tomás Saraceno (2016/2017), licensed under CC BY‑SA 4.0, via Aerocene.org.

Tomás Saraceno

Argentine contemporary artist Tomás Saraceno’s Aerocene is a visionary art project that combines art, science, and environmental advocacy. Launched in 2015 during the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21) in Paris, Aerocene consists of a series of airborne sculptures, that are essentially large, balloon-like aerosolar vessels, that lift off the ground using only the heat of the sun and the air currents, without any fossil fuels, engines, or even helium and using recyclable materials.

With this, it invites scientists, engineers, and the public to collaborate on developing aerosolar flight technology. The Aerocene balloons have set world records for solar flight and have even lifted human passengers (in 2020, the Aerocene Pacha carried a person aloft without propane or engines, a first in aviation). In artistic terms, Saraceno extends the legacy of art-utopias like Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic visions or Ant Farm’s inflatable structures, but grounds it in climate urgency.

Aerocene

Tomás Saraceno

Argentine contemporary artist Tomás Saraceno’s Aerocene is a visionary art project that combines art, science, and environmental advocacy. Launched in 2015 during the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21) in Paris, Aerocene consists of a series of airborne sculptures, that are essentially large, balloon-like aerosolar vessels, that lift off the ground using only the heat of the sun and the air currents, without any fossil fuels, engines, or even helium and using recyclable materials.

(2015–ongoing, global project)

They work in a way that during the daytime, the solar radiation heats the air inside, which makes them rise, and at night, they can drift on thermal currents. These poetic floating pods are envisioned to be the “longest, most sustainable journey around the world,” carried only by wind and sun. Conceptually, Aerocene is as much about community and open innovation as it is about the physical sculptures. It operates as an open-source project and a movement for a fossil-free future.

Image Source: “Fly with Aerocene Pacha” by Studio Tomás Saraceno / Aerocene Foundation, licensed under CC BY‑SA 4.0

Photo of the Aerocene Backpack by Studio Tomás Saraceno (2016/2017), licensed under CC BY‑SA 4.0, via Aerocene.org.

With this, it invites scientists, engineers, and the public to collaborate on developing aerosolar flight technology. The Aerocene balloons have set world records for solar flight and have even lifted human passengers (in 2020, the Aerocene Pacha carried a person aloft without propane or engines, a first in aviation). In artistic terms, Saraceno extends the legacy of art-utopias like Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic visions or Ant Farm’s inflatable structures, but grounds it in climate urgency.

Aerocene

(1967/1974)

This jarring juxtaposition of eternal beauty and everyday waste is the artist’s sharp critique of modern consumer society: the motley heap of cast-off textiles signifies pollution, poverty, and decay converging with the idealized figure of Venus.

Image Source: Michelangelo Pistoletto, Venus of the Rags, 1967 Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

Image from the Smithsonian Institution

Michelangelo Pistoletto

In Pistoletto’s iconic Venus of the Rags, a life-sized classical Venus stands with her back turned to a towering pile of discarded rags and old clothes.

Pistoletto’s installation forces viewers to confront the “accumulated rubbish of contemporary society” looming over a symbol of perfection, essentially holding up a mirror to our throwaway culture and its values.

Venus of the Rags

(1967/1974)

This jarring juxtaposition of eternal beauty and everyday waste is the artist’s sharp critique of modern consumer society: the motley heap of cast-off textiles signifies pollution, poverty, and decay converging with the idealized figure of Venus.

Image Source: Michelangelo Pistoletto, Venus of the Rags, 1967 Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

Image from the Smithsonian Institution

Michelangelo Pistoletto

In Pistoletto’s iconic Venus of the Rags, a life-sized classical Venus stands with her back turned to a towering pile of discarded rags and old clothes .

With this, it invites scientists, engineers, and the public to collaborate on developing aerosolar flight technology. The Aerocene balloons have set world records for solar flight and have even lifted human passengers (in 2020, the Aerocene Pacha carried a person aloft without propane or engines, a first in aviation) . In artistic terms, Saraceno extends the legacy of art-utopias like Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic visions or Ant Farm’s inflatable structures, but grounds it in climate urgency.

Venus of the Rags

Michelangelo Pistoletto

In Pistoletto’s iconic Venus of the Rags, a life-sized classical Venus stands with her back turned to a towering pile of discarded rags and old clothes.

(1967/1974)

This jarring juxtaposition of eternal beauty and everyday waste is the artist’s sharp critique of modern consumer society: the motley heap of cast-off textiles signifies pollution, poverty, and decay converging with the idealized figure of Venus .

Image Source: Michelangelo Pistoletto, Venus of the Rags, 1967 Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

Image from the Smithsonian Institution

Pistoletto’s installation forces viewers to confront the “accumulated rubbish of contemporary society” looming over a symbol of perfection, essentially holding up a mirror to our throwaway culture and its values .

Venus of the Rags

(2011–13)

Titled This is Not a Fountain as a nod to Magritte, the piece uses objects bearing the dents and wear of daily life, speaking to the economic realities of their former owners and the vast rural-to-urban migration in India.

Image source: MUSEUM MMK FÜR MODERNE KUNST Frankfurt am Main, © MMK/Schneider

Subodh Gupta

Indian artist Subodh Gupta repurposes battered metal pots, pans, and water vessels collected from families across India into a cascading installation that resembles a gushing fountain.

The addition of circulating water running through the piled pots “raises the specter of competition over increasingly scarce natural resources,” confronting viewers with issues of water scarcity amid industrialization . Gupta’s work thus transforms household waste into a poignant commentary on social change and ecological urgency.

This is Not a Fountain

(2011–13)

Titled This is Not a Fountain as a nod to Magritte, the piece uses objects bearing the dents and wear of daily life, speaking to the economic realities of their former owners and the vast rural-to-urban migration in India.

Image source: MUSEUM MMK FÜR MODERNE KUNST Frankfurt am Main, © MMK/Schneider

Subodh Gupta

Indian artist Subodh Gupta repurposes battered metal pots, pans, and water vessels collected from families across India into a cascading installation that resembles a gushing fountain.

The addition of circulating water running through the piled pots “raises the specter of competition over increasingly scarce natural resources,” confronting viewers with issues of water scarcity amid industrialization . Gupta’s work thus transforms household waste into a poignant commentary on social change and ecological urgency.

This is Not a Fountain

Subodh Gupta

Indian artist Subodh Gupta repurposes battered metal pots, pans, and water vessels collected from families across India into a cascading installation that resembles a gushing fountain.

(2011–13)

Titled This is Not a Fountain as a nod to Magritte, the piece uses objects bearing the dents and wear of daily life, speaking to the economic realities of their former owners and the vast rural-to-urban migration in India.

Image source: MUSEUM MMK FÜR MODERNE KUNST Frankfurt am Main, © MMK/Schneider

The addition of circulating water running through the piled pots “raises the specter of competition over increasingly scarce natural resources,” confronting viewers with issues of water scarcity amid industrialization . Gupta’s work thus transforms household waste into a poignant commentary on social change and ecological urgency.

This is Not a Fountain

(2017)

In a remarkable sustainable practice, he often reuses the same bamboo strips for multiple installations in fact, the bamboo in The Gate at The Met had already been used in ten previous works, including one at the Guimet Museum in Paris.

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV, The Gate (2017), tiger bamboo. Lent by the artist. Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Open Access).

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV’s The Gate is a sprawling, site-specific installation woven entirely from tiger bamboo. A fourth-generation Japanese bamboo artist, Tanabe harvests fast-growing bamboo and ingeniously moistens and bends each strip to create twisting forms that meld floor to ceiling.

This monumental artwork marries traditional craft with contemporary scale, showing how a renewable natural material can be continually regenerated into new sculptural life while retaining the spirit of its cultural origins.

The Gate

(2017)

In a remarkable sustainable practice, he often reuses the same bamboo strips for multiple installations in fact, the bamboo in The Gate at The Met had already been used in ten previous works, including one at the Guimet Museum in Paris.

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV, The Gate (2017), tiger bamboo. Lent by the artist. Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Open Access).

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV’s The Gate is a sprawling, site-specific installation woven entirely from tiger bamboo. A fourth-generation Japanese bamboo artist, Tanabe harvests fast-growing bamboo and ingeniously moistens and bends each strip to create twisting forms that meld floor to ceiling.

This monumental artwork marries traditional craft with contemporary scale, showing how a renewable natural material can be continually regenerated into new sculptural life while retaining the spirit of its cultural origins.

The Gate

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV’s The Gate is a sprawling, site-specific installation woven entirely from tiger bamboo. A fourth-generation Japanese bamboo artist, Tanabe harvests fast-growing bamboo and

ingeniously moistens and bends each strip to create twisting forms that meld floor to ceiling.

(2017)

In a remarkable sustainable practice, he often reuses the same bamboo strips for multiple installations in fact, the bamboo in The Gate at The Met had already been used in ten previous works, including one at the Guimet Museum in Paris.

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV, The Gate (2017), tiger bamboo. Lent by the artist. Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Open Access).

This monumental artwork marries traditional craft with contemporary scale, showing how a renewable natural material can be continually regenerated into new sculptural life while retaining the spirit of its cultural origins.

The Gate

(2010)

Constructed from hundreds of discarded plastic bottles Wang gathered from Beijing’s dumps (with a few foreign bottles mixed in), the inverted whirl of colorful debris rises three floors high in a dramatic twist. This finely sculpted whirlwind of trash is both a sobering commentary on the environmental impact of China’s rapid development and, conversely, an awe-inspiring symbol of the nation’s colossal power and influence.

Images: Wang Zhiyuan, Thrown to the Wind (2010). Images Source: wangzhiyuanart.com

Wang Zhiyuan

Beijing-based artist Wang Zhiyuan gives form to China’s plastic pollution crisis with Thrown to the Wind, an enormous 11-meter-tall “tornado” of trash swirling up through a multi-story gallery space.

By literally elevating waste into the realm of art, Wang confronts viewers with the scale of global plastic excess and China’s role in that story.

Thrown to the Wind

(2010)

Constructed from hundreds of discarded plastic bottles Wang gathered from Beijing’s dumps (with a few foreign bottles mixed in), the inverted whirl of colorful debris rises three floors high in a dramatic twist. This finely sculpted whirlwind of trash is both a sobering commentary on the environmental impact of China’s rapid development and, conversely, an awe-inspiring symbol of the nation’s colossal power and influence.

Images: Wang Zhiyuan, Thrown to the Wind (2010). Images Source: wangzhiyuanart.com

Wang Zhiyuan

Beijing-based artist Wang Zhiyuan gives form to China’s plastic pollution crisis with Thrown to the Wind, an enormous 11-meter-tall “tornado” of trash swirling up through a multi-story gallery space.

By literally elevating waste into the realm of art, Wang confronts viewers with the scale of global plastic excess and China’s role in that story.

Thrown to the Wind

Wang Zhiyuan

Beijing-based artist Wang Zhiyuan gives form to China’s plastic pollution crisis with Thrown to the Wind, an enormous 11-meter-tall “tornado” of trash swirling up through a multi-story gallery space.

(2010)

Constructed from hundreds of discarded plastic bottles Wang gathered from Beijing’s dumps (with a few foreign bottles mixed in), the inverted whirl of colorful debris rises three floors high in a dramatic twist. This finely sculpted whirlwind of trash is both a sobering commentary on the environmental impact of China’s rapid development and, conversely, an awe-inspiring symbol of the nation’s colossal power and influence.

Images: Wang Zhiyuan, Thrown to the Wind (2010). Images Source: wangzhiyuanart.com

By literally elevating waste into the realm of art, Wang confronts viewers with the scale of global plastic excess and China’s role in that story.

Thrown to the Wind

(2010 - Today)

Her works often resemble bioluminescent sea creatures or dreamlike abstract flora, which serves as a reminder that our life choices have consequences on the environment. The artworks were exhibited internationally as they exemplify how trash can become treasure.

Image: Aurora Robson, images form the artist (aurorarobson.com).

Aurora Robson

Aurora Robson creates intricate hanging sculptures by intercepting the plastic waste stream, producing artworks that are as beautiful as they are thought-provoking. The Canadian-American artist meticulously collects and cleans discarded plastic from bottles to bucket lids to later reassemble them into colorful, whimsical, nature-inspired forms.

It invites viewers to a playful elegance of reflecting on plastic’s persistent presence in our lives and encourages a shift toward responsibility and sustainability.

Sculptures from Plastic Debris

(2010 - Today)

Her works often resemble bioluminescent sea creatures or dreamlike abstract flora, which serves as a reminder that our life choices have consequences on the environment. The artworks were exhibited internationally as they exemplify how trash can become treasure.

Image: Aurora Robson, images form the artist (aurorarobson.com).

Aurora Robson

Aurora Robson creates intricate hanging sculptures by intercepting the plastic waste stream, producing artworks that are as beautiful as they are thought-provoking. The Canadian-American artist meticulously collects and cleans discarded plastic from bottles to bucket lids to later reassemble them into colorful, whimsical, nature-inspired forms.

It invites viewers to a playful elegance of reflecting on plastic’s persistent presence in our lives and encourages a shift toward responsibility and sustainability.

Sculptures from Plastic Debris

Aurora Robson

Aurora Robson creates intricate hanging sculptures by intercepting the plastic waste stream, producing artworks that are as beautiful as they are thought-provoking. The Canadian-American artist meticulously collects and cleans discarded plastic from bottles to bucket lids to later reassemble them into colorful, whimsical, nature-inspired forms.

(2010 - Today)

Her works often resemble bioluminescent sea creatures or dreamlike abstract flora, which serves as a reminder that our life choices have consequences on the environment. The artworks were exhibited internationally as they exemplify how trash can become treasure.

Image: Aurora Robson, images form the artist (aurorarobson.com).

It invites viewers to a playful elegance of reflecting on plastic’s persistent presence in our lives and encourages a shift toward responsibility and sustainability.

Sculptures from Plastic Debris

(2017)

Viewers can walk inside this winding, tunnel-like environment, surrounded by undulating layers of repurposed wood that swell and bulge like a living organism. By giving new life to the “cheap wood…commonly used to obscure construction sites” , Oliveira’s work physically embodies urban renewal and decay.

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV, The Gate (2017), tiger bamboo. Lent by the artist. Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Open Access).

Henrique Oliveira

Brazilian artist Henrique Oliveira’s immersive installation Transarquitetônica transforms weathered construction debris into a cavernous artwork. Oliveira salvages discarded plywood planks (tapumes) from São Paulo’s torn-down fencing and nails these broken wood pieces onto an organic framework, creating what looks like a tangle of giant roots snaking through the gallery.

It merges painting, sculpture, and architecture – visually echoing brushstrokes of Abstract Expressionism – to illustrate how something broken and cast off can regenerate into a vibrant, enveloping landscape .

Transarquitetônica

(2016)

Mahama “extricates these jute sacks from their utilitarian life cycle and transposes them into the world of art,” charging them with political meaning as records of human toil in global trade.

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV, The Gate (2017), tiger bamboo. Lent by the artist. Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Open Access).

Ibrahim Mahama

Ghanaian artist Ibrahim Mahama creates monumental installations out of old jute sacks that once carried goods like cocoa, coffee, or coal. In works such as Fracture, thousands of stained, tattered jute sacks, each stamped “Produce of Ghana” and bearing the grime and repairs of hard use, are stitched together and draped over architectural spaces.

By blanketing museum walls or entire buildings with this rough patchwork, he exposes the often-invisible labor and inequities behind commodities, while also giving these cast-off textiles a new life.

The striking contrast between the elegant gallery setting and the sacks’ ragged texture creates a tension that compels us to consider the true cost of our material consumption.

Fracture

(2010s)

Afterwards, these are used to create vivid abstract paintings with the reclaimed pigments. Each pigment swirls in a composition that embodies an act of environmental remediation.

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV, The Gate (2017), tiger bamboo. Lent by the artist. Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Open Access).

John Sabraw

American artist John Sabraw literally paints with pollution and transforms toxic waste into art. He, in a collaboration with environmental engineers, harvests iron oxide pigments from polluted streams in Ohio, then goes through a process of removing metallic toxins from the water (which is then returned clean to the ecosystem) and yielding rich ochre and red pigments to be mixed into the artist’s paints.

John Sabraw’s artworks are a tangible upcycling industrial pollution into art, which goes to demonstrate an innovative regeneration that draws attention to contaminants that are rather unseen, while physically turning an ecological problem into a creative solution.