Merken magazine

Life Imitates Art

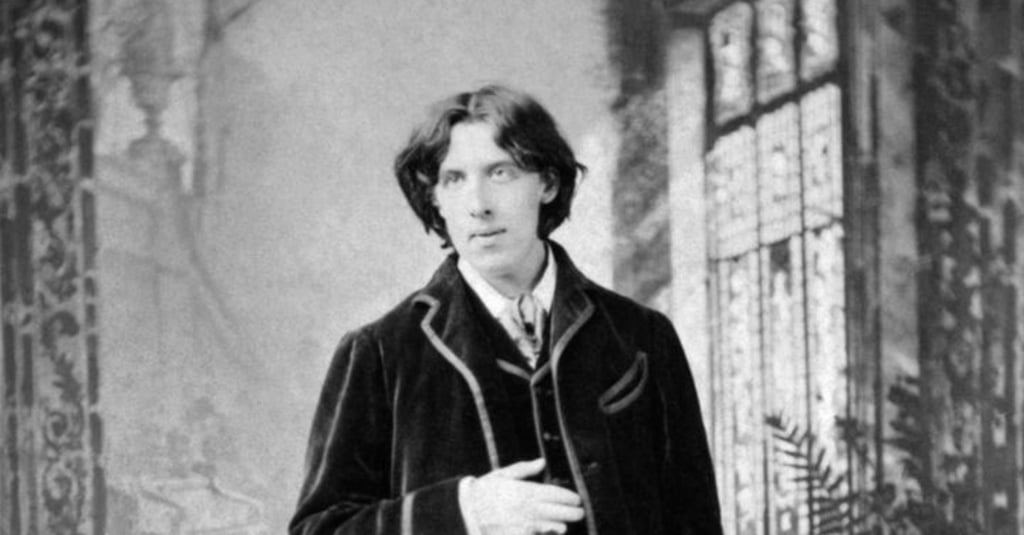

Art doesn't just mirror life, rather it defines it. The angle from which we see and live life was once ink on a poem line, or some paint on a brush. From the way we see beauty to how we experience love. Explore the meaning behind the famous quote by Oscar Wilde "life imitates art far more than art imitates life," and discover how creativity andartistic expressions define the world we live in.

ARTLITERATURE

Ayoub Iken

3/3/20255 min read

Mimesis and anti-mimesis exist at the same time

Art is often seen as the echo of life, but life in turn reflects art. While life provides the materials, that is experience, emotions, landscapes, and struggles, art transforms them into expressions, giving them form, permanence, and meaning. Stories influence our perceptions, paintings define aesthetics and beauty, a photograph has the power to dictate how history is remembered, and films set off cultural movements. Therefore, artistic expressions influence our understanding and interpretations of the world.

The anti-mimesis philosophy, as expressed by Oscar Wilde in his essay The Decay of Lying (1891), "Life imitates art far more than art imitates life," challenges the commonly held and traditional belief that art is a mere reflection of reality. the quote views art, like culture and language, as a tool human perception. In other words, Wildean beliefs hold that art is no longer defined by life and reality, it doesn’t strive to reflect life’s ideals and virtues, and that art is not a passive mimicking of life but an active force that conditions and forms our experiences, interpretations, and interactions. Everything, from emotions, behaviors, and beauty perception, to historical events and interpretations, is not understood because of some inherent qualities, but because a poem, a painting, or a book has taught us to see it that way. Artists do not copy what exists how it simply exists, they highlight, distort, and reimagine: the sea is a spirit, a city is an organism, and a flower is her.

Shockingly enough, Oscar Wilde’s essay begins with a classical version of the “Touch Grass” meme, to which the character Vivian explains that there is no pure perception of nature, and the world is already shaped by art. This can still be seen in today’s “go out and touch grass” meme, which is not a call to return to an untouched and real, as in non-virtual, reality, but a request to return to a pre-constructed aesthetic, curated by centuries of artistic influence and deemed realistic. However, mimesis and realism are a mere reproduction of what already exists, missing the purpose of art which is to be creative and to imagine new possibilities. In all fairness, mimetic art does influence our perception as it reinforces what already exists and makes us more aware of issues in the world, yet to Oscar Wilde it restricts what could be.

Realism is an artificial construct that Wilde would argue is less useful of a style, despite having the term “real” in it, the art genre was heavily idealized and culturally constructed. Orientalists, for instance, claimed to depict the “real” Middle East and Africa, yet they showed a fantastic and fabricated idea of the East, which as a result shaped the West’s perception of the Orient. Another example would be the royal portraits compared to their descriptions, capturing kings and queens like Louis XIV, Elizabeth I, and Henry VIII was often riddled with grandeur, idealization, and religious symbolism that shaped how people perceived monarchy, contradicting how others described them in terms of both features and characteristics. Even modern photojournalism involves subjective choices in terms of framing, lighting, and editing that pretend to simply capture reality, something we all know is not always true. To Wilde, art that copies reality is just artistically lying while claiming not to.

The Debate

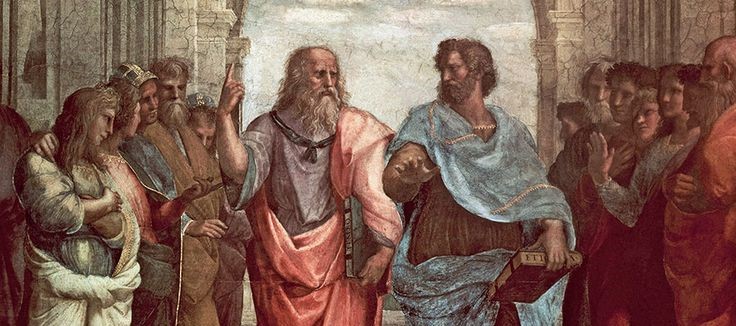

Mimesis (art imitating life) and anti-mimesis (life imitating art) is a centuries-old debate. The classical Greek philosopher Plato holds that art imitates life, but he sees this imitation as problematic for it can be deceiving. He believes that art, by imitating the physical world, is twice removed from the truth. Ironically, Plato’s fear of art made him ban poets and artists from his ideal city because they might influence society. Yet, wasn’t he an artist imagining an ideal city in the first place?

His student Aristotle had a more positive perspective of mimesis. He saw life’s imitation in art as a valuable tool and a core human aspect for understanding life and emotional well-being. He worte in his book ‘Poetics’: "Imitation is natural to man from childhood, one of his advantages over the lower animals being this, that he is the most imitative creature in the world, and learns at first by imitation. And it is also natural for him to delight in works of art."

Oscar Wilde then birthed anti-mimesis, flipping the relationship between art and life on its head. He declares through his character Vivian that "Life holds the mirror up to Art, and either reproduces some strange type imagined by painter or sculptor, or realizes in fact what has been dreamed in fiction." Wilde positions art as the model by which we interpret life and experience reality, and art for him does not reflect reality but creates it.

If Oscar Wilde’s idea seems extreme, then you haven’t heard of Jean Baudrillard’s theory of hyperreality. Baudrillard proposes that life imitates art to an extent where reality itself becomes a simulation, exemplifying it through Disneyland, which he described as a simulacrum, a copy with no original.

What Does Life Have to Say About This?

Life craves art’s expression, and maybe it doesn’t want to only be observed but elevated and transformed. As Wilde suggested, things truly come into existence because we see them, with the act of seeing, not simply looking but truly seeing, life, nature, and things become alive. Our perception of landscapes, beauty, and seasons, for example, is shaped by how artists portrayed them, how the poets described solitude, how painters depicted love, and how cinema portrayed rebellion. Would Paris be considered “romantic” if poems, films, and novels never framed it as such? Would we experience heartbreak the same way if not for love songs and poetry? And what would Halloween look like if not for horror movies and gothic literature? Art, therefore, has always dictated how we see the world, how we see life.

Art for Art’s Sake

Oscar Wilde is a notable figure in aesthetics, and his ideas reflect the artistic movement’s beliefs that value beauty and artistic expression over moral, political, or ethical concerns. He rejected the idea that the value of art lies in its social impact or the lesson it may or may not teach, believing that art’s value exists in the form and the presentation itself. Although Wilde famously expressed the power of art, acknowledging its inevitable influence, he opposed the imposition of a social responsibility and moral duty on artists. The role of an artist for Wilde is free from a utilitarian function, believing the form of the artistic expression is above the message an artwork may disseminate, and that art loses its essence when it becomes a preaching and propaganda tool. To him, art shouldn’t force a message, artists should create freely without social constraints and art should simply exist, and with time, life naturally takes it in and shapes how we see the world.

We Reference Art More Than We Think in Our Daily Lives

If you look closely at your daily activities, you’ll find art silently influencing your behaviors. It is in the architectural movements that make your dream home, the poetry-derived metaphors you use to communicate, your fashion selections, and the angles and lights in your selfies. Art, thus, is the reference.

The School of Athens 1509–1511 by Raphael

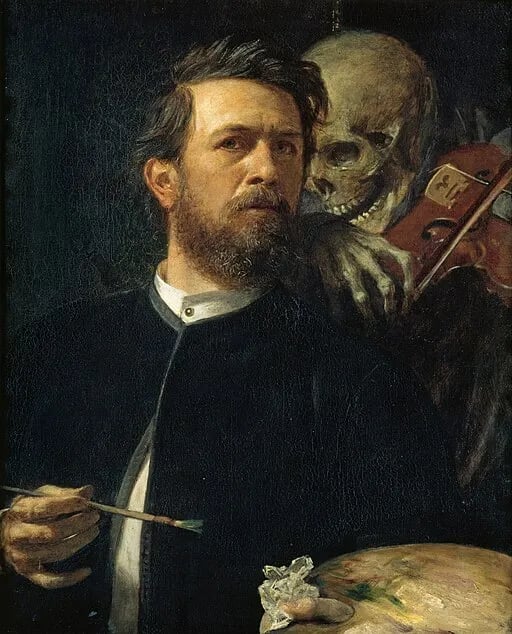

Self-Portrait with Death Playing the Fiddle 1872 by Arnold Böcklin